By: Ollus Ndomu

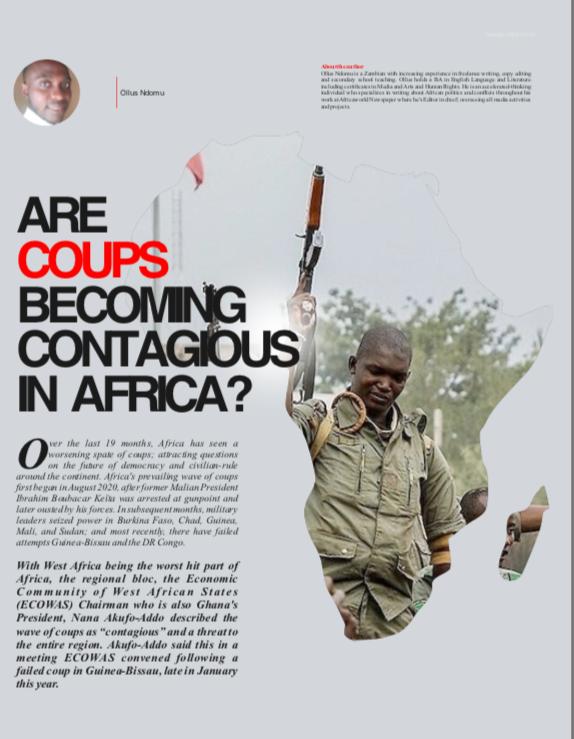

Over the last 19 months, Africa has seen a worsening spate of coups; attracting questions on the future of democracy and civilian-rule around the continent. Africa’s prevailing wave of coups first began in August 2020, after former Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta was arrested at gunpoint and later ousted by his forces. In subsequent months, military leaders seized power in Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea, Mali, and Sudan; and most recently, there have failed attempts Guinea-Bissau and the DR Congo.

With West Africa being the worst hit part of Africa, the regional bloc, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Chairman who is also Ghana’s President, Nana Akufo-Addo described the wave of coups as “contagious” and a threat to the entire region. Akufo-Addo said this in a meeting ECOWAS convened following a failed coup in Guinea-Bissau, late in January this year.

Although all these coups share some commonalities including political and economic instability and weak democratic institutions, Joseph Sany, vice president at the US Institute of Peace’s Africa Center, told Vox in a phone interview that referring to African coups as “contagious” is unhelpful.

Sany argues that specific circumstances in each coup are crucial to understanding what happened and what follows; justifying his argument on the basis that the circumstances and mechanics of each African coup and attempt is different from others:

“I hate the term ‘contagion’ because it’s a blanket term. You can’t put Guinea in the same group as Mali and Burkina Faso.”

Mechanics of Africa’s Current Coups

Background events, circumstances and hindsight show that political and economic instability, corruption, ethnic politics and weak democratic institutions are major factors fueling the comeback of coups around Africa. Take for example Mali and Burkina Faso, military take-overs occurred when governments focused more on combating ISIS extremism and al-Qaeda affiliates around the Sahel region, leaving both countries’ socio-economic problems unaddressed. In a co-written 2020-2021 report on coups in Africa, Joseph Siegle, research director at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, revealed that attacks by militant Islamist organizations had increased from 1,180 to 2,005 in the Sahel region.

Though Siegle acknowledges the toll of increased attacks on the region’s economy, he believes that the security threat formed a pretext for successful coups in Mali and Burkina Faso:

“In terms of the differences, [in] Mali and Burkina Faso, the juntas have claimed that insecurity and an inability to deal with threats from violent extremist groups has precipitated the coups.”

“They’re both using the same justification, and in the case of Burkina Faso, the threat is more imminent,” Siegle adds.

While terror affiliates inspire instability Africa as expressed by Siegle, violent insurgency by terror groups cannot be entirely generalized as the factor behind all recent coups.

Guinea-Bissau’s attempted coup best exemplifies this line of argument. A relatively peaceful country survived a military take-over late in January this year. Even without an apparent violent insurgency by terror groups, the military tried to copycat other junta leaders have successfully done their countries.

A successful last September Guinea military power grab, presents another dimension of coup mechanics in West Africa. Former President Alpha Condé raped the country’s constitution in addition to disadvantaging opponent in his successful bid for a third term in office. Although Condé came into office through the first ever Guinean democratic elections in 2010 vote — his third term power grab, coupled with deep inequality and corruption, imbued the military with impetus to callously overthrow him.

Chad is another unique coup case study; its 2021 military takeover following the death of President Idriss Deby in a battle with rebels, opens us to a new dimension of this phenomenon. After Deby’s demise Chad’s military led a “covert coup”, installing his son, also a military commander, as the leader in violation of the constitution. Junior Deby’s government is supposed to be “transitional” — his father was Chad’s authoritarian leader for three decades — but since it abolished the constitution and dissolved the previous government and Parliament, it’s not clear where such a transition could lead, Ellen Loanes –Vox.

Is Contagious the right term for these coups?

Making reference to the circumstances and mechanics forming a pretext for each failed and successful coup, the word ‘contagious’ is certainly not the right term. Calling this spate of coups “contagious” plays down the complexity of the problem. More so, it rebates the influence of foreign powers including France, Russia, China and Turkey and some Gulf states. These powers never foment coups in Africa but they capitalize on instability to bankroll regimes in pursuit to legitimize their own anti-democratic systems and consolidate their influence. These nations portray themselves as Africa’s big brothers but their entire interest is to extract resources such as diamonds, gold, emerald, bauxite, and other valuable materials.

This finds better expression in Siegle’s comment on Guinea military power grab:

“It fits the mould of situations where you have an unelected, unaccountable military leader who doesn’t have a lot of political support, so, make him indebted to the Russians.”

“They’ll get access to their iron ore, and [a military leader will] give them political cover. So I see them as very vulnerable to that kind of influence.”

Mucus Leuyeh, an official and researcher at the US Institute of Peace’s Africa Center holds similar views as he said:

“If you want to know where Russia will go next, look for instability.” He pointed out that Mali’s junta, though faced with increasing insecurity from Islamist extremism, receives mercenaries from the Russian Wagner Group. Given the West African country’s status quo, this arrangement could potentially erode the junta’s ability to provide essential services to the peace, further worsening the prevailing social, political and economic instability. Moreover, the ripple effect of the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as anti-French, anti-colonial sentiment, are slowly building up into an explosive cocktail.

Are Coup Leaders Pursuing a Reformist Agenda?

In each power grab, juntas have cited security crisis, political instability and lack of leadership to address national socio-economic problems. Even though military leaders have been so savvy to institute coups, are doing nothing different from those they dislodge from power. All countries now under the military power grab spell, have continued to grapple with political and economic instability and weak democratic institutions.

In the latest forum discussion on African coups organized by the US Institute of Peace’s Africa Center, Sany said, “The coup leaders themselves aren’t necessarily saying what they’re going to do differently, and I think that the similarity that we’re seeing across all the coups is these military actors, which all happen to be mid-level, colonel-level military leaders, they all seem more intent on seizing power and holding power for power’s sake.”

Siegle holds similar views: “They’re not offering some sort of reformist agenda, a security plan, somehow a return to democracy or improving government, or reducing corruption — anything along those lines,” quoted from Vox interview.

Though coup leaders continue to promise people a return to democracy and economic stability, Naunihal Singh, a professor at the US Naval War College, thinks otherwise. In his publication, In Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups, Singh wrote, “Coups are responsible for roughly 75% of democratic failures, making them the single largest danger to democracy.”

Sany observes that international punitive actions taken against coup leaders as in the case of Mali, do not change anything but harm the citizens, further pushing civilians away from political leadership. He adds that blanket sanctions are not viable pathways for a transition to democracy: “By putting on blanket sanctions, you alienate and punish citizens.” Overall, sanctions do not address underlying causes of instability, but precipitate further instability that may potentially result into more power struggles within the ruling junta.

All and above, it is appropriate to conclude that coups do not spell the reformation Africa needs but rather breed more instability, worse than the current status quo. Individual countries and regional bodies must not look to condemn juntas without having addressed the root cause. Africa needs peace, Africa needs industrial revolution and unity of purpose.