By: Ollus Ndomu

By: Ollus Ndomu

In recent weeks, the renowned author and academic Siddharth Kara released his latest book, Cobalt Red: How the Congo Powers our Lives. The book sheds light on the labor conditions and living standards in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where cobalt mining is prevalent. Cobalt is a crucial metal in the global energy transition, and the book argues that Western consumers who use products containing Congolese cobalt are complicit in a human rights and environmental catastrophe.

The book has received widespread acclaim in the US and UK, becoming a New York Times bestseller in its first week of release. Publishers Weekly has hailed it as a “tour de force exposé,” and Foreign Affairs has called it “a thorough and insightful investigation.” Kara was even invited to discuss the book on the Joe Rogan podcast, which has garnered over four million views on YouTube in just one month. The book has also been featured in major news outlets such as CNN, Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the Daily Mail.

Commenting on the book’s wide readership in the West, journalist Howard French once said, “It allows us, meaning the general public [in the US], to become interested in Africa in ways that respond to some pre-existing notions we have of Africa. That Africa should be a certain kind of way. That Africa should provide an escalating sense of horror in order to get us interested in it.”

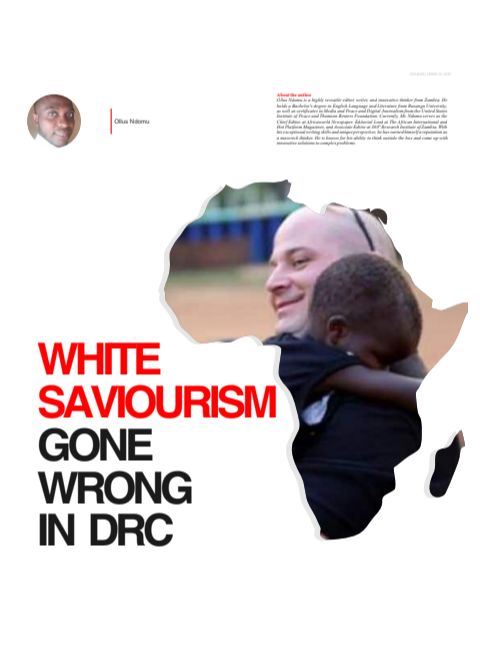

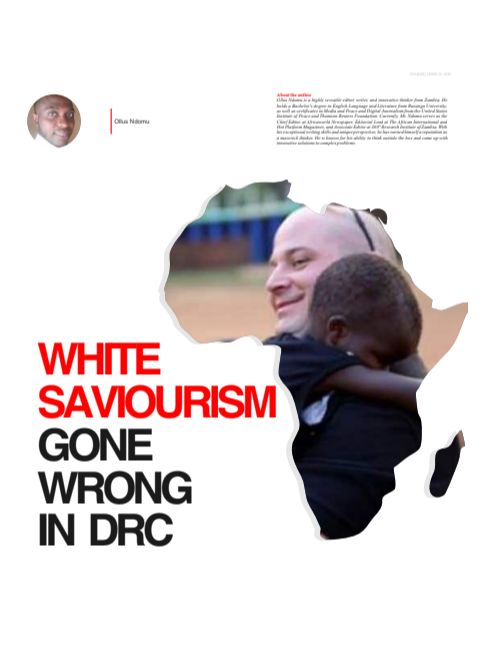

True to French’s opinion, the book has garnered widespread attention in America and Europe, quickly becoming a bestseller and receiving accolades from numerous publications. Kara has even been invited to speak about the book on a popular podcast. However, the book’s popularity stems from its ability to tap into pre-existing Western perceptions of Africa. Cobalt Red employs vivid language and imagery to evoke sympathy for the Congolese people.

Unfortunately, the book follows a well-worn narrative of Western writers traveling to Africa to tell stories that paint the continent as a place of suffering and despair. This narrative also perpetuates the idea that the Western world is the only hope for Africa. This is a grossly unfair portrayal of Africa, as the continent is not helpless and does not need saving by the West.

While Cobalt Red has brought much-needed attention to the plight of cobalt miners in the Congo, it is crucial to remember that Africa is not a continent in need of rescue by the West. We must be mindful of falling into the trap of viewing Africa solely through a lens of suffering and despair.

Nothing New, History Repeating Itself

Kara’s story follows the same pattern as the conflict minerals playbook from the 2000s, which did not end well. Christoph Vogel’s Conflict Minerals Inc. delves into the multiple drivers of violence in the Congo, unlike the simplistic single narratives that Western advocacy on “conflict minerals” relied on. These colonial frames led to policies that perpetuated structural violence, and the crude misrepresentation of conflict in the eastern Congo as being driven by greedy warlords trying to access minerals fed into equally blunt policies that harmed many of the people they sought to support.

However, the reality was that mining was the largest employer in the region after agriculture, and for all the mine sites with links to conflict financing, there were just as many without such links. These mines provided a vital source of income to hundreds of thousands of workers and their households, often at a wage level higher than available alternatives and in a context of widespread local unemployment. Unfortunately, these nuances did not fit into stereotypical Western stories or the simplistic campaign against conflict minerals, which drove down demand for eastern Congolese minerals. The impact of this on people in the region was severe, sustained, and widespread. Meanwhile, the conflict itself continued unabated, making international headlines in recent months with the resurgence of M23.

It is crucial to understand local mining in the Congo as Wainaina’s landscape in which people laugh, struggle, and make do in usually mundane circumstances, rather than Kara’s “grim wasteland of utter ruin.” Otherwise, history will repeat itself, and the impact on people in the region will be severe, sustained, and widespread. Western tech and electric vehicle companies always put their faith in foreign-owned industrial mines or dubious mineral traceability and certification schemes to secure Congolese cobalt, which only soothes their consciences.